One of my favorite “trick” questions is “what is the length

of the East Coast of the US?”

First, you may question does it stop at the

Texas/Mexico border or the tip of Florida, and what about Key West? A bit more

challenging is what about the Chesapeake Bay, and all those rivers? But let’s

assume you get past those.

An engineer may just approximate it as 103 miles,

because we are trained to do a quick approximation to test more detailed

calculations J.

But let’s go with a more experimental approach.

Looking at a map of the whole US and using a 1’ ruler you get one,

approximate, length. But using a 1” ruler and you get a longer length. Now go to

the individual state maps and do the same exercise: yet longer lengths. What

about county maps: longer yet.

Now try walking it, probably better for an armchair

experiment, you get longer and longer lengths the shorter your ruler. Consider

what length you get if your ruler is a grain of sand. What about a

Silicon-Dioxide molecule? …

This is the “Coastline Paradox.”

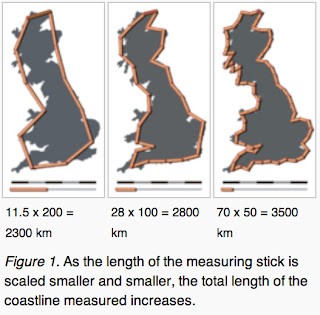

The problem is that coastlines are fractal-like. So the

shorter the measure you use, the longer the total length (true fractals have

infinite length J).

This highlights a key difference between constructed items

and natural items: constructed regular edges vs. irregular and even changing

edges (think about the effect of tides on your coastline measurements). Consider a road vs. a path, a chair vs. a rock, or a swimming pool vs. a

pond.

This poses a critical problem for conventional maps, which

expect things to be regular and constant (yes they are making progress with

traffic, but that is only statistical or sampled). Thus maps do pretty well for

roads and buildings (except for example in Death

Valley), but not so well for hiking and kayaking (we regularly have to turn

back on what the GPS map shows as navigable streams, or even half a lake

overgrown with weeds!).

We paddled on a very nice stream, but the topological map of

course didn’t show the 7 beaver dams of various heights, but it did show 3

non-existent islands.

So one of the challenges in our new mapping approach is to

represent the irregular and changing natures of many of the items we encounter

in real life, as opposed to the smooth regular features of artificial constructs,

such as roads, although even those are marred by reality, such as pot holes

appearing and growing, construction, collisions, and of course traffic.

No comments:

Post a Comment